The Chicago Tribune ran a story on drunk driving arrests on December 19, 2011. The article discusses how the numbers of arrests for driving under the influence statewide have decreased over several years.

A few points from the article should be examined.

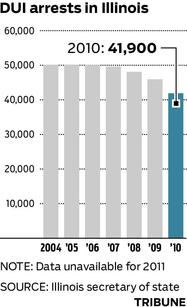

First, the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) reports that from 2007 through 2010, arrests for DUI have fallen 16 percent. Additionally, the number of fatal accidents related to alcohol have decreased 33 percent.

The debate is whether these decreases can be attributed to tougher DUI laws or some other cause. Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) says that the increase in penalties for DUI caused the reduction in arrests. People, they say, are getting the message.

But history does not tell the same story.

Illinois lowered the legal limit from 0.10 to 0.08 in 1997. Coincidentally, the number of arrests for DUI in 1996, prior to the change, was 44,710. After 0.08 became law, the number of arrests increased to almost 50,000 in 1999.

Statewide, the number of arrests for DUI in Illinois stayed constant at approximately 50,000 until 2008, the beginning of the recession.

The history lesson in these numbers is that fewer people are being arrested for DUI because fewer people drink at bars and restaurants because they cannot afford to go out. Attorney Donald Ramsell makes this point in his interview to the Trib.

Nonetheless, anti-drunk driving advocates from MADD and the Secretary of State want to take credit for the reduction in numbers. Susan McKeigue, the executive director of MADD in Illinois, notes that a person who gets a DUI is now thought of as a “pariah” under these new tough laws.

One of these new laws is the Monitoring Device Driving Permit (MDDP), which went into effect on January 1, 2009. A person who blows 0.08 or refuses the breathalyzer gets a statutory summary suspension of his driver’s license. However, that person may drive during the suspension after installing a Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Device (BAIID) in the vehicle. The device makes sure that the person’s breath alcohol concentration is less than 0.05 before the vehicle can start.

Illinois lawmakers, judges, prosecutors, and police officers expected this new law would be a game-changer. But they were surprised to find that few drivers applied for the permit. According to the Secretary of State, less than 12,000 drivers have participated in the program, a fraction of those who are eligible.

To my knowledge, consumer electronics giant Best Buy was a provider for the device in 2009 and 2010. Drivers could get the BAIID installed at their local Best Buy outlet. But Best Buy stopped selling the BAIID because nobody bought it.

The MDDP law teaches us a lesson about Illinois DUI law and politics in general. First, like so many other state-approved programs, the question is why was only a small number of companies approved to manufacture the BAIID? The exclusive license to make BAIIDs for this program should have been very lucrative. Just like the Chicago parking meter contract, the deal stinks of back room trades and under the table dealing.

It turns out the BAIID license was not lucrative. The Chicago Tribune should have followed up on the issue and explained how the lobbying groups for these BAIID companies attempted in 2010 to secure a mandatory $750 fee from each driver found guilty of DUI that would go into an ‘indigent driver MDDP’ fund. Lobbyists were pushing for this law because the participation rate in the MDDP program was so low. They figured if indigent defendants (eg, those with public defenders) could have their MDDPs subsidized, then more people would participate in the program.

A $750 assessment against all defendants would have been a windfall for the BAIID companies. Like so many things in DUI, the BAIID program is an initiative with a good purpose that has been overshadowed by a pursuit of profits.

I have no problem with the message from MADD that ‘drunk driving kills.’ But they should be honest and admit, ‘not all the time.’ First-time DUI offenders are punished too severely. And all too often, law enforcement programs are obsessed with profits over good policy.